Curt Chiarelli

Yog-Sothothery on the Fly

Apropos to the spirit of the Witching Season, I'd like to introduce everyone here to a very important, yet totally obscure, figure in the world of not only figurative sculpting, but also human anatomy studies: the 17th century master technician and father of the modern anatomical model, Gaetano Guilio Zummo.

Born in Syracusa, Sicily in 1665 to a wealthy, aristocratic family. He studied in a Jesuit monastery and was expelled for undisclosed reasons. He moved to Naples and then Bologna where the first school of cereplastics was founded near an anatomical institute. From there he moved to Florence to work under Cosimo III de Medici. When he abruptly left his service, Cosimo was quoted as saying, "You may very well find a greater patron, but never will you find one who understands or appreciates your worth as much as I". From there he headed to Genoa to work with the noted French surgeon Guillarme Desnoues on several wax models. Another falling out in 1700 ended this association too and he then headed north to Marseilles, France at the invitation of the court of Louis XIV. Although we know virtually nothing of the man or his character, reading between the lines of these collective incidents, apparently Gaetano was a formidible man of some stubborness and pride. His reputation while an employee under Louis XIV reached its zenith just before his death from a cerebral haemorrhage 1701.

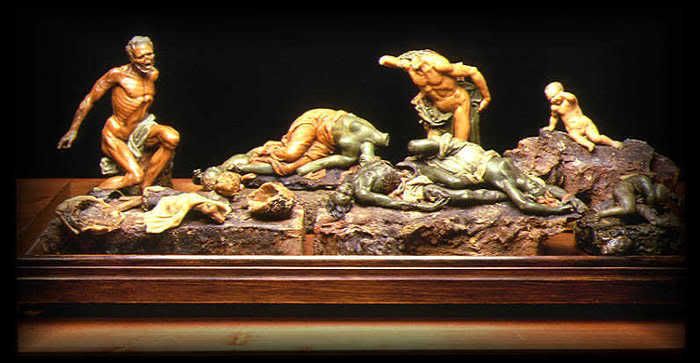

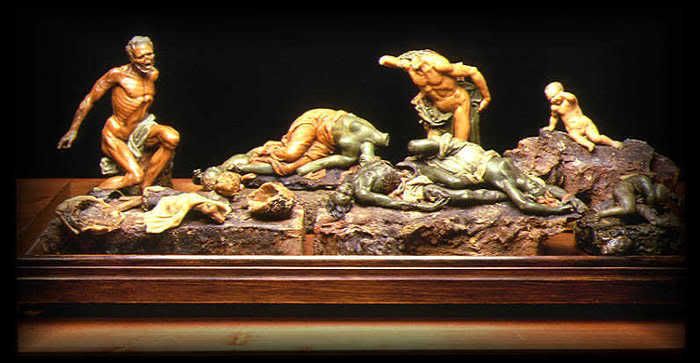

Gaetano's work can be broken down into two distinct phases: his purely scientific anatomical models and his later "teatrini" or dioramas which ruminated upon the subject of man's transcience.

When looking at his teatrini, a modern audience must keep in mind the necessity of judging his work within the context of the era and cultural milieu in which he lived. 300 years ago the experience of death and corruption (as opposed to the sanitized, distanced and highly attenuated incarnations our society deals in) were as commonplace as hamburger franchise outlets in ours. Executed criminals were left to hang on gibbetts outside the gates of most major cities. The wealthy and powerful were interred under the floor of churches and their stench making Sunday worship at times difficult for parishioners. Many monuments and headstones had memento mori reminding the living of the frailty of man. Visions of the Danse Macabre (or in its German translation, "Totentanz") paraded across tapestries, woodblock illustrations, murals and public sculptures. Innumerable wars, famines and plague epidemics ravaged Europe. Gaetano's art merely reflected the times in which he lived, and were not necessarily the expression of a diseased mind or one overtly fixated upon morbid subject matter.

After his death, his work was distributed throughout Europe in various collections of the nobility, largely forgotten and shuttered away due to their grotesque subject matter until the Marquis De Sade revived some interest in them when he himself wrote of the experience - the "fearful truth" - of viewing his works. Some of his models found a home at the Museo di Storia della Scienza in Florence. In 1966 a violent rainstorm damaged several of his models, some beyond repair. Another, "Il Morbo Gallico" was entirely destroyed in the basement where it was stored when the River Arno flooded.

Although he's been demoted to less than a footnote in the annals of art history Gaetano's reputation deserves much better than his current fate. Anyone who has studied this masterpiece of biological engineering called the human body will attest that an understanding of its structures and their relationships to one another is greatly enhanced through the use of 3-dimensional models as opposed to flat 2-dimensional diagrams. His technical mastery of cereplastics, moldmaking and casting were as legendary as they were innovative and his work ranks him with another brilliant artist of the Neo-Classical Period, Clemente Susini.

Although wax has been used as a modeling material since before the dawn of recorded time, Gaetano's use of differently coloured waxes for ecorche models that could be disassembled predated this practice by a full century. Later generations owe a debt of gratitude to him.

Born in Syracusa, Sicily in 1665 to a wealthy, aristocratic family. He studied in a Jesuit monastery and was expelled for undisclosed reasons. He moved to Naples and then Bologna where the first school of cereplastics was founded near an anatomical institute. From there he moved to Florence to work under Cosimo III de Medici. When he abruptly left his service, Cosimo was quoted as saying, "You may very well find a greater patron, but never will you find one who understands or appreciates your worth as much as I". From there he headed to Genoa to work with the noted French surgeon Guillarme Desnoues on several wax models. Another falling out in 1700 ended this association too and he then headed north to Marseilles, France at the invitation of the court of Louis XIV. Although we know virtually nothing of the man or his character, reading between the lines of these collective incidents, apparently Gaetano was a formidible man of some stubborness and pride. His reputation while an employee under Louis XIV reached its zenith just before his death from a cerebral haemorrhage 1701.

Gaetano's work can be broken down into two distinct phases: his purely scientific anatomical models and his later "teatrini" or dioramas which ruminated upon the subject of man's transcience.

When looking at his teatrini, a modern audience must keep in mind the necessity of judging his work within the context of the era and cultural milieu in which he lived. 300 years ago the experience of death and corruption (as opposed to the sanitized, distanced and highly attenuated incarnations our society deals in) were as commonplace as hamburger franchise outlets in ours. Executed criminals were left to hang on gibbetts outside the gates of most major cities. The wealthy and powerful were interred under the floor of churches and their stench making Sunday worship at times difficult for parishioners. Many monuments and headstones had memento mori reminding the living of the frailty of man. Visions of the Danse Macabre (or in its German translation, "Totentanz") paraded across tapestries, woodblock illustrations, murals and public sculptures. Innumerable wars, famines and plague epidemics ravaged Europe. Gaetano's art merely reflected the times in which he lived, and were not necessarily the expression of a diseased mind or one overtly fixated upon morbid subject matter.

After his death, his work was distributed throughout Europe in various collections of the nobility, largely forgotten and shuttered away due to their grotesque subject matter until the Marquis De Sade revived some interest in them when he himself wrote of the experience - the "fearful truth" - of viewing his works. Some of his models found a home at the Museo di Storia della Scienza in Florence. In 1966 a violent rainstorm damaged several of his models, some beyond repair. Another, "Il Morbo Gallico" was entirely destroyed in the basement where it was stored when the River Arno flooded.

Although he's been demoted to less than a footnote in the annals of art history Gaetano's reputation deserves much better than his current fate. Anyone who has studied this masterpiece of biological engineering called the human body will attest that an understanding of its structures and their relationships to one another is greatly enhanced through the use of 3-dimensional models as opposed to flat 2-dimensional diagrams. His technical mastery of cereplastics, moldmaking and casting were as legendary as they were innovative and his work ranks him with another brilliant artist of the Neo-Classical Period, Clemente Susini.

Although wax has been used as a modeling material since before the dawn of recorded time, Gaetano's use of differently coloured waxes for ecorche models that could be disassembled predated this practice by a full century. Later generations owe a debt of gratitude to him.