Yes -- by the way, another interesting bit from these critical editions comes from

Tolkien on Fairy-Stories -- Tolkien knew M. R. James's

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, arguably the best collection of ghost stories in the language. In case anyone's interested, I'll post a couple of things that I wrote for the fine Tolkien newsletter

Beyond Bree

http://www.cep.unt.edu/bree.html

on the matter.

TOLKIEN AND M. R. JAMES AND J. S. LE FANU

Not long ago I wrote about 19th- and 20th-century influences on Tolkien for Routledge’s

Tolkien Encyclopedia. If I had known then that the professor was acquainted with M. R. James’s

Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904), I’d have proposed the barrow-wight episode in

The Fellowship of the Ring as a passage showing possible “influence.” I’ve only just found out about Tolkien’s awareness of this volume of James’s tales, from the new critical edition of

On Fairy-Stories prepared by Verlyn Flieger and Douglas A. Anderson (London: Harper Collins, 2008; Tolkien’s very brief reference is on page 261).

James wrote four collections of ghost stories, concluding the series in 1925. His stories eschew the conventional Victorian trappings. There are no translucent shades pointing woefully at wall panels or desks that conceal documents whose disclosure will at last secure peace for the dead, justice for the innocent, or punishment for the guilty. However, there is a convincing atmosphere of scholarship in these stories by James (1862-1936), who was a medievalist and the translator of the so-called “New Testament Apocrypha.” He is best known, though, for his ghost stories. The “Jamesian tradition” that developed eventually included collections of stories by R. H. Malden, A. N. L. Munby, L. T. C. Rolt, and others.

Throughout James’s four books, the “ghost” is generally not a specter, but kin to the

draug of Norwegian and Icelandic lore: it is undead, repulsive of appearance, tangible, murderous, and perhaps the guardian of buried treasure or a haunter connected with some ancient object. The entity in “’Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,’” perhaps James’s most famous story, is associated with a centuries-old whistle, while the “ghost” in “A Warning to the Curious” guards an ancient crown buried in the sand. Some of James’s “ghosts,” such as the one in “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book,” are like demons in medieval art, or may be tentacled monstrosities, such as the pursuer in “Count Magnus.” Often the Jamesian “ghost” is an active but frightfully emaciated corpse. In the first collection of stories, “The Ash-Tree” provides not only a horribly withered undead attacker, but, interestingly, some large, disgusting spiders, which the creator of “Old Tomnoddy, all big body” in

The Hobbit would have appreciated.

The Jamesian ghost is usually

glimpsed, or at least not described extensively. The protagonists, scholarly bachelors who, like hobbits, have no desire for excitement, quite often escape having experienced nothing worse than a bad scare. One reason the stories are appealing to many readers is that they combine a sophisticated tone of pedantry with a basically schoolboyish spookery. James censured the introduction of excessive gruesomeness and of sexuality into the ghost story. Effects should be nicely calculated, he wrote in a 1929 essay. “Malevolence and terror, the glare of evil faces, 'the stony grin of unearthly malice', pursuing forms in darkness, and 'long-drawn, distant screams', are all in place, and so is a modicum of blood, shed with deliberation and carefully husbanded; [but] the weltering and wallowing that I too often encounter merely recall the methods of M. G. Lewis.” The loathsome and the dreadful are to be evoked,

tastefully, as a mere “peep into Pandemonium.” The object is entertainment, and it was as entertainments that James read some of his tales to intimate audiences on Christmas Eve.

James was an admirer of the ghost stories of the Irish-born Victorian author Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), and edited a collection of his magazine work as

Madame Crowl’s Ghost and Other Tales of Mystery (1923). Le Fanu’s novel

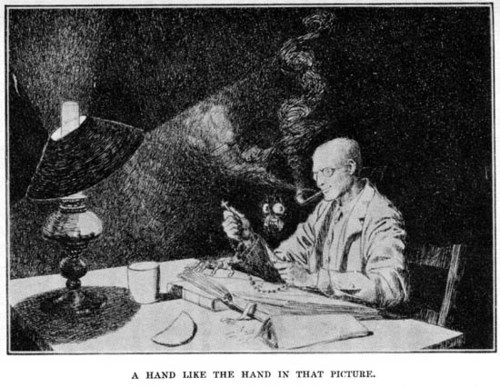

The House by the Churchyard contains a short story, “The Authentic Narrative of the Ghost of a Hand,” that is sometimes published independently. A household is terrorized by a hand.

“There was a candle burning on a small table at the foot of the bed, beside the one [Mr. Prosser] held in one hand […]. He drew the curtain at the side of the bed, and saw Mrs. Prosser lying, as for a few seconds he mortally feared, dead, her face being motionless, white, and covered with a cold dew; and on the pillow, close beside her head, and just within the curtains, was, as he first thought, a toad—but really the same fattish hand, the wrist resting on the pillow, and the fingers extended towards her temple.” It transpires that Mrs. Prosser was in a “trance,” and afflicted by horrifying visions or nightmares, while the hand was there.

One wonders if Tolkien might have come across this story at some time before writing “Fog on the Barrow-Downs.”* In that chapter, Frodo, Merry, Sam and Pippin are drawn into a burial mound, and the latter three are cast into a spellbound sleep, somewhat as Mrs. Prosser is. Frodo sees a “long arm… groping, walking on its fingers towards Sam, who was lying nearest.” Frodo grabs a sword and attacks the arm, “and the hand broke off.” Tom Bombadil rescues the hobbits, but as Frodo leaves the barrow he thinks he sees “a severed hand wriggling still.” As if adapting James’s technique, Tolkien provides very little description of the haunter.

So far as I know, Tolkien had no special interest in or liking for ghost stories, but the barrow-wight episode, with its aura of antiquity, and the physical appearance and custodial character of the glimpsed “wight,” recalls the standard Jamesian scenario. The sequence, Tom Shippey has written in

The Road to Middle-earth, “could almost be omitted without disturbing the rest of the plot.”** Its inclusion inserted a Jamesian entertainment into

The Lord of the Rings; it is an adventure that lacks the sense of seriousness that develops as the great narrative continues.

Notes

*The creeping hand in the barrow may have originated in young Michael Tolkien’s dream of “a gloved hand without an arm that opened curtains a crack after dark and crawled down the curtain.” Tolkien made a colored drawing of this hand, called

Maddo, in 1928 (Hammond and Scull:

J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator, pp. 83-84). Of course it’s just possible that young Michael’s dream derived from a reading of Le Fanu’s story, or a retelling of it.

**The barrow-wight episode provides Merry with the sword with which he stabs the chief of the Ringwraiths in

The Return of the King; no other blade, we are told, could have dealt the Witch-King so bitter a wound, “cleaving the undead flesh, breaking the spell that knit his unseen sinews to his will.” However, Éowyn’s sword-thrust is the

coup de grace. The reader may wonder if the detail about Merry’s blade was a not entirely convincing ploy intended to justify retention of a passage not really integral to the book.

One might consider a more positive take on the episode. We know that the Barrow-wight dates back to a Bombadil poem written before

The Lord of the Rings. We see Tolkien drawing up, into the more serious morality of

LOTR, material that could indeed be -- for the most part -- integrated into it because it readily related itself to the key theme of the spiritual danger of acquisitiveness. It was appropriate to bring in this theme in an early adventure that was commensurate with the "hobbitry" of the opening chapters. It's as if Tolkien resourcefully, though not perhaps completely, assimilated and transformed the Jamesian entertainment, whose spooks are often possessive beings, for the purposes of

LOTR, after having responded imaginatively to it just as amusing creepiness that left a trace in the early Bombadilia.

[FONT="] [/FONT]

I recall, they wore little more than g-strings, and harnesses or belts for carrying weapons.

I recall, they wore little more than g-strings, and harnesses or belts for carrying weapons.