Extollager

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2010

- Messages

- 9,271

Daily Mail columnist Peter Hitchens hasn't forgotten Doyle's first Challenger story:

31 August 2012 3:10 PM

A Truly Lost World

Each time I re-read my favourite thriller The Rose of Tibet by Lionel Davidson, I am caught by a few words as the hero (if such he is) recalls ‘rapt, jammy evenings by the fire with the “Children’s Encyclopaedia”’ or something very like that.

This reminiscence is prompted by his first real experience of Tibet itself, which makes him realise coldly how far from home he is. Davidson never went there, and simply imagined it from books and maps, rather convincingly in my view. But what would I know? I haven’t managed to get to Tibet either, only to Bhutan next door.

He is no doubt recalling blurred, greenish photographs of monks and other Tibetans, large men blowing huge horns, monasteries clinging to high hillsides, and ancient, incomprehensible ceremonies under the mighty walls of Lhasa.

My view of the world was largely formed by Arthur Mee’s books, some in a holiday home we used to rent in West Wittering (later made notorious by Marianne Faithfull, but then a most respectable seaside resort), some on shelves in my grandfather’s eccentric home in Portsmouth, with its piles of defunct fretwork wireless sets, its mangle and its air-raid shelter too solid to be demolished.

Outside it is a chilly grey day in Southern England, lapped in safety. The great moat of the sea is just to the south. The soft shapes of the Downs are to the north. England is secure, prosperous, solid and unchanging. And here in these cramped pages are pictures and accounts of an exotic, impossibly distant world inhabited by, well, foreigners and strange wild beasts.

There, there is no safety, no moat against invasion and the hand of war, and there are jagged, unfriendly mountains and sucking, snake-infested swamps instead of soft sheep-cropped hills and quiet woodlands. There is adventure, uncertainty, excitement – all the things that are not to be found in the comfortable counties served by the dark green trains of the Southern Region of British Railways.

This picture of abroad, as it turned out, was truer than I knew, and I have been privileged to see for myself many of the places those ancient encyclopaedias first alerted me to. I wlll never get over my visit to Kashgar, or my first sight of the Himalayas, or of Persepolis. But alongside it ran the memory of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s book ‘the Lost World’ (whose title was borrowed by Michael Crichton a few years ago, surely consciously. It must be 50 years since I read this book, and the other day I turned to it again.

I was surprised both by what I remembered and what I didn’t. Three particular moments I recalled as if I had read them yesterday. Other scenes were vaguely familiar. Others were wholly unfamiliar. I knew the names of all the major characters, especially of Professor Challenger, a character Doyle invented, I think, as part of his struggle to escape the monster of Sherlock Holmes, which he had created but could not control, and of Lord John Roxton, who I am told may have been modelled on the sad figure of Sir Roger Casement.

I would be surprised if it is read at all any more – not because it isn’t a great story, for it is. The party set out to find a remote plateau in South America where dinosaurs and pterodactyls still dwell. You’ll have to read it to find out what happens. But it is of course dogged by the racial stereotypes of its time -1912. So it is full of expressions and sentiments which no modern teacher or librarian could permit.

It is also, like the now-dead Boy’s Own Paper and the Children’s Newspaper of my boyhood, written in a complex, literate style which Doyle assumed would be accessible and normal for boys as young as nine or ten.

Yet it has lived in my memory for half a century, and may well have helped stimulate the mind of the man who wrote Jurassic Park and so gave the modern world its own enthralling chance to imagine what would happen if modern man met living dinosaurs.

http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/

......Extollager notes: My son once spotted a copy of The Lost World with photos tied to the 1920s silent movie -- in a recycle bin. What a find!

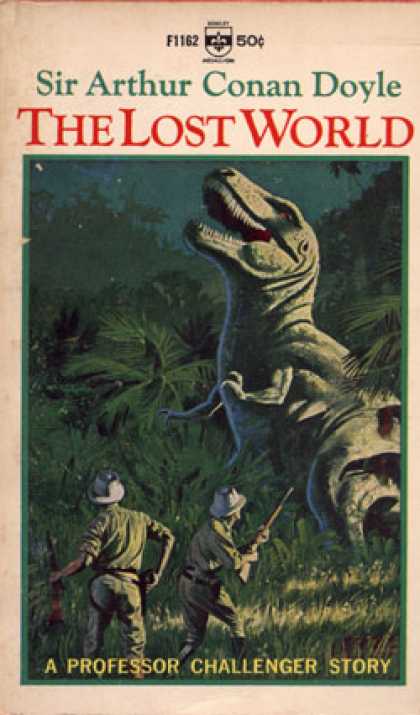

The Lost World in an edition like this was one of the first items in my personal science fiction collection.

31 August 2012 3:10 PM

A Truly Lost World

Each time I re-read my favourite thriller The Rose of Tibet by Lionel Davidson, I am caught by a few words as the hero (if such he is) recalls ‘rapt, jammy evenings by the fire with the “Children’s Encyclopaedia”’ or something very like that.

This reminiscence is prompted by his first real experience of Tibet itself, which makes him realise coldly how far from home he is. Davidson never went there, and simply imagined it from books and maps, rather convincingly in my view. But what would I know? I haven’t managed to get to Tibet either, only to Bhutan next door.

He is no doubt recalling blurred, greenish photographs of monks and other Tibetans, large men blowing huge horns, monasteries clinging to high hillsides, and ancient, incomprehensible ceremonies under the mighty walls of Lhasa.

My view of the world was largely formed by Arthur Mee’s books, some in a holiday home we used to rent in West Wittering (later made notorious by Marianne Faithfull, but then a most respectable seaside resort), some on shelves in my grandfather’s eccentric home in Portsmouth, with its piles of defunct fretwork wireless sets, its mangle and its air-raid shelter too solid to be demolished.

Outside it is a chilly grey day in Southern England, lapped in safety. The great moat of the sea is just to the south. The soft shapes of the Downs are to the north. England is secure, prosperous, solid and unchanging. And here in these cramped pages are pictures and accounts of an exotic, impossibly distant world inhabited by, well, foreigners and strange wild beasts.

There, there is no safety, no moat against invasion and the hand of war, and there are jagged, unfriendly mountains and sucking, snake-infested swamps instead of soft sheep-cropped hills and quiet woodlands. There is adventure, uncertainty, excitement – all the things that are not to be found in the comfortable counties served by the dark green trains of the Southern Region of British Railways.

This picture of abroad, as it turned out, was truer than I knew, and I have been privileged to see for myself many of the places those ancient encyclopaedias first alerted me to. I wlll never get over my visit to Kashgar, or my first sight of the Himalayas, or of Persepolis. But alongside it ran the memory of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s book ‘the Lost World’ (whose title was borrowed by Michael Crichton a few years ago, surely consciously. It must be 50 years since I read this book, and the other day I turned to it again.

I was surprised both by what I remembered and what I didn’t. Three particular moments I recalled as if I had read them yesterday. Other scenes were vaguely familiar. Others were wholly unfamiliar. I knew the names of all the major characters, especially of Professor Challenger, a character Doyle invented, I think, as part of his struggle to escape the monster of Sherlock Holmes, which he had created but could not control, and of Lord John Roxton, who I am told may have been modelled on the sad figure of Sir Roger Casement.

I would be surprised if it is read at all any more – not because it isn’t a great story, for it is. The party set out to find a remote plateau in South America where dinosaurs and pterodactyls still dwell. You’ll have to read it to find out what happens. But it is of course dogged by the racial stereotypes of its time -1912. So it is full of expressions and sentiments which no modern teacher or librarian could permit.

It is also, like the now-dead Boy’s Own Paper and the Children’s Newspaper of my boyhood, written in a complex, literate style which Doyle assumed would be accessible and normal for boys as young as nine or ten.

Yet it has lived in my memory for half a century, and may well have helped stimulate the mind of the man who wrote Jurassic Park and so gave the modern world its own enthralling chance to imagine what would happen if modern man met living dinosaurs.

http://hitchensblog.mailonsunday.co.uk/

......Extollager notes: My son once spotted a copy of The Lost World with photos tied to the 1920s silent movie -- in a recycle bin. What a find!

The Lost World in an edition like this was one of the first items in my personal science fiction collection.