Matteo

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 8, 2012

- Messages

- 1,383

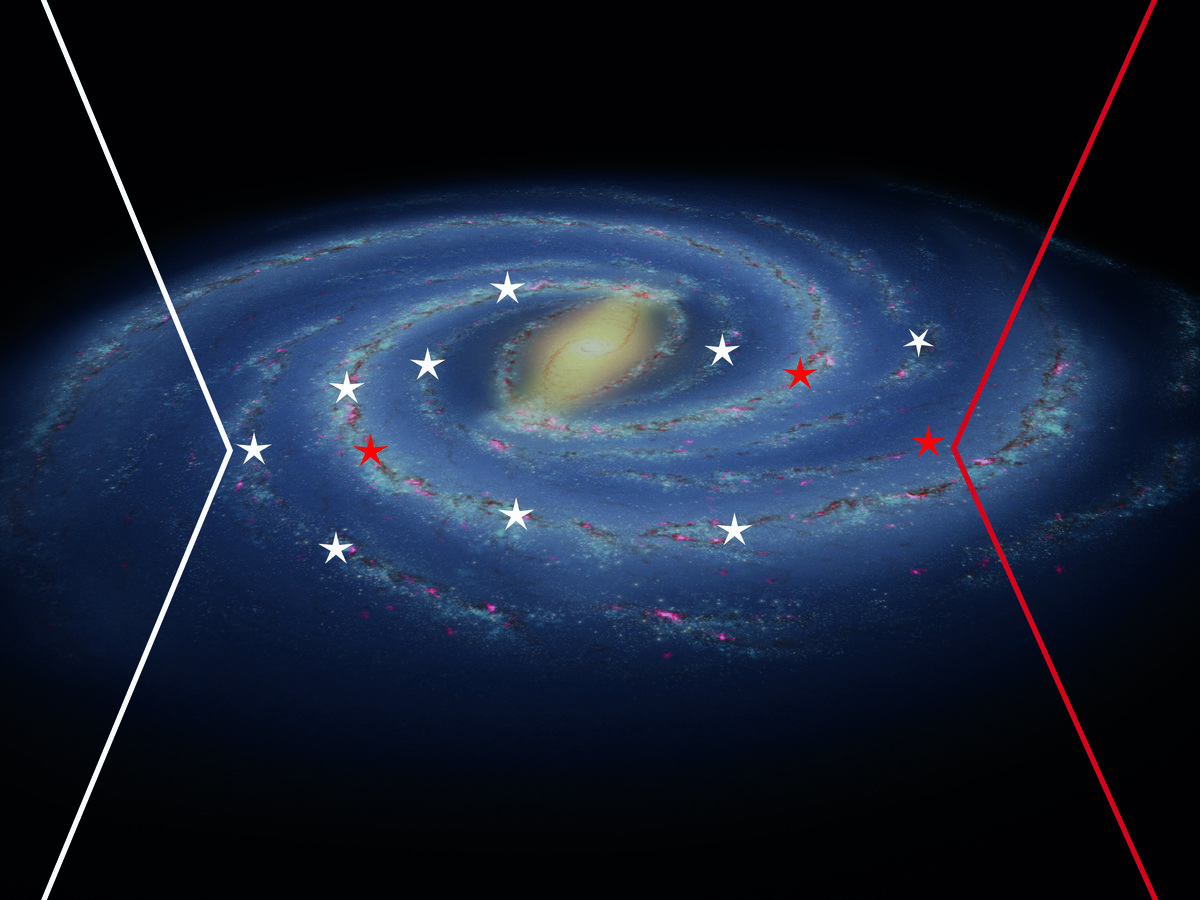

Astronomers led by Maria Bergemann (Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy) have performed chemical measurements on stars that could markedly change the way cosmologists measure the Hubble constant and determine the amount of so-called dark energy in our universe. Using improved models of how the presence of chemical elements affects a star’s spectrum, the researchers found that so-called supernovae Type Ia have different properties than previously thought. Based on assumption about their brightness, cosmologists have used those supernovae to measure the expansion history of the universe. In light of the new results, it is now likely those assumptions will need to be revised.

And the original article: https://www.mpg.de/14550374/original_article.pdf

And the original article: https://www.mpg.de/14550374/original_article.pdf