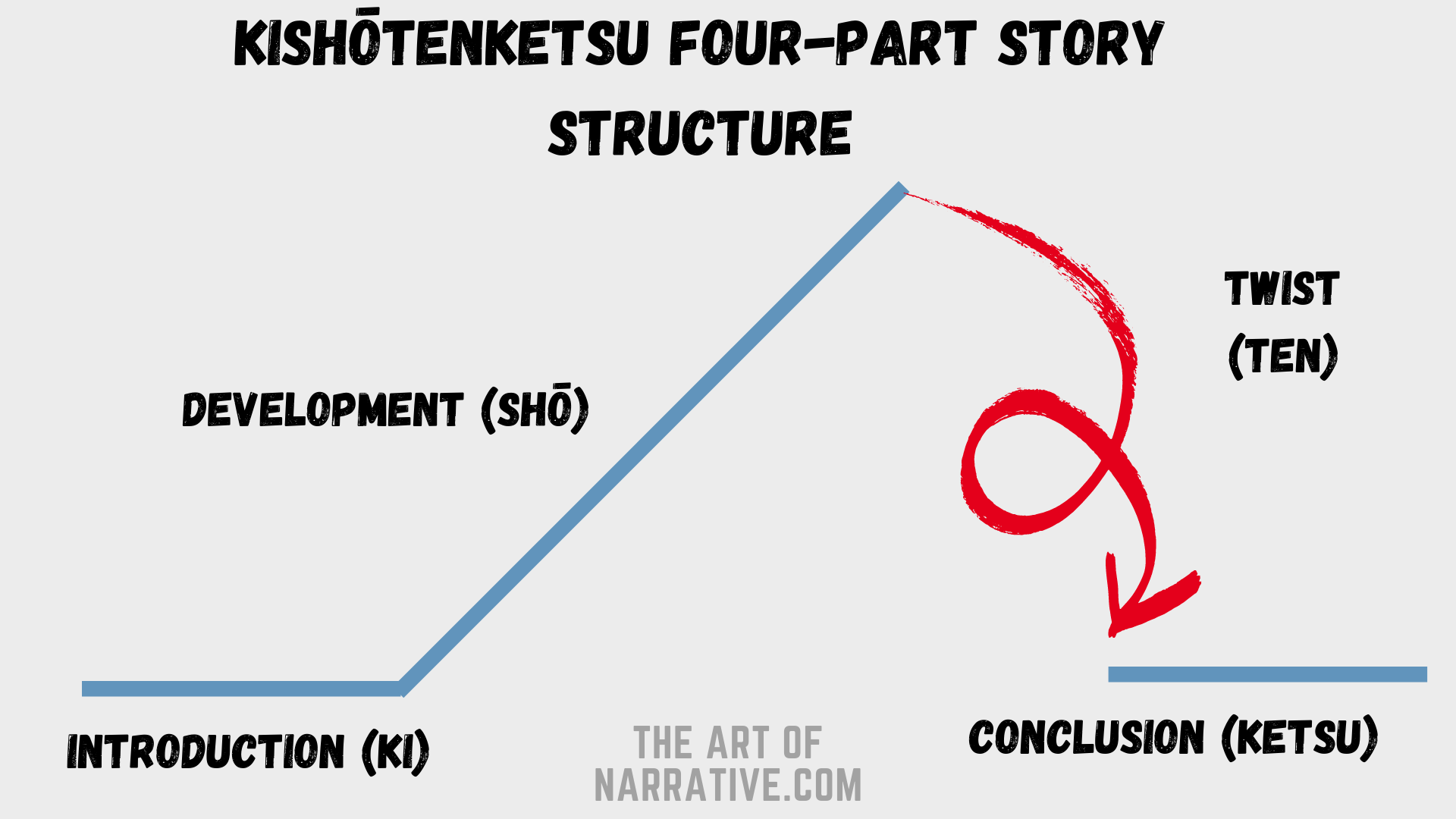

alexvss posted a link to a nice resource in a recent profile post, which highlights a key difference between Western and Asian story structure. Simply put, while

modern Western stories often focus on conflict, where a protagonist has to overcome adversity to get what they want. Asian story structures instead focus on a twist in the 3rd act which changes everything.

Here's a good starter article about it:

artofnarrative.com

artofnarrative.com

Of course, there are a lot of generalizations going on here. However, I'm still struck by the story structure in the Anime film Your Name, which uses the third act twist to brilliant effect.

I thought some people might find this helpful as something to look into, because while a strong twist has often been used in short stories, it's tended not to be a main feature of Western novels.

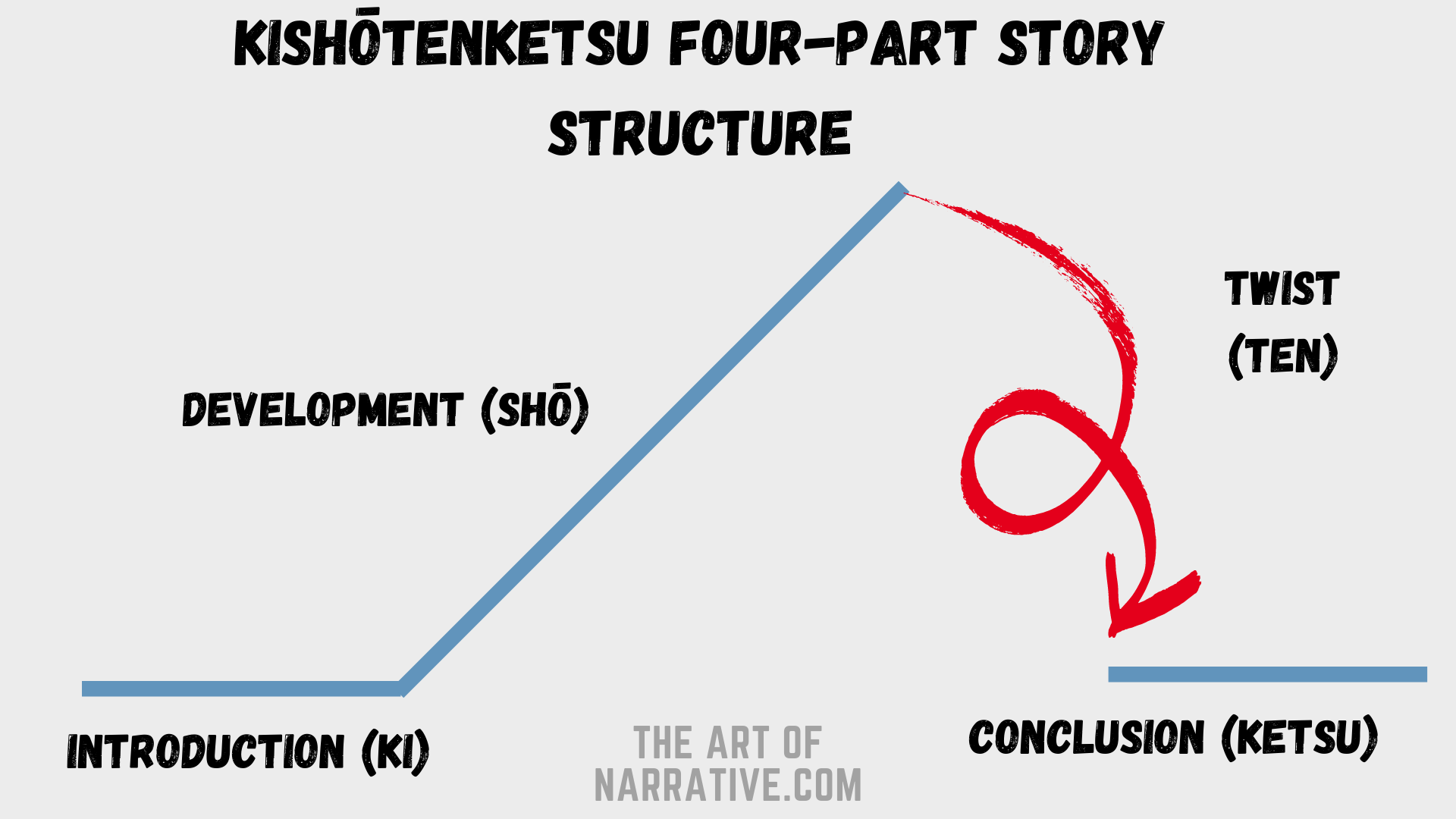

modern Western stories often focus on conflict, where a protagonist has to overcome adversity to get what they want. Asian story structures instead focus on a twist in the 3rd act which changes everything.

Here's a good starter article about it:

Kishōtenketsu: Exploring The Four Act Story Structure - The Art of Narrative

Kishōtenketsu is a story told in four parts. Kishōtenketsu is a Japanese story structure that doesn’t need conflict to work. Learn to write without conflict

artofnarrative.com

artofnarrative.com

Of course, there are a lot of generalizations going on here. However, I'm still struck by the story structure in the Anime film Your Name, which uses the third act twist to brilliant effect.

I thought some people might find this helpful as something to look into, because while a strong twist has often been used in short stories, it's tended not to be a main feature of Western novels.