Extollager

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2010

- Messages

- 9,271

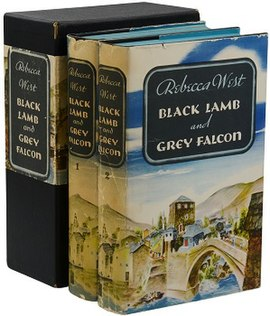

I've been wanting to read Rebecca West's massive 1941 book (it's two volumes of about 600 pages each in the edition I intend to read) for years. Notes should be appearing here as I go along. Will anyone join me? It is a journey in Yugoslavia in 1937. One critic whom I respect says it is the greatest book of the 20th century.

The New York TImes reviewer wrote:

"Black Lamb and Grey Falcon" bears the travel-book subtitle of "A Journey Through Yugoslavia," and it follows with consummate success the travel-book formula of history and description and characterization on a thread of personal experience. But it is safe to say that as a travel book it is unique. In two almost incredibly full-packed volumes one of the most gifted and searching of modern English novelists and critics has produced not only the magnification and intensification of the travel book form, but, one may say, its apotheosis. Rebecca West's "Journey Through Yugoslavia" is carried out with tireless percipience, nourished from almost bewildering erudition, chronicled with a thoughtfulness itself fervent and poetic; and it explores the many-faceted being of Yugoslavia -- its cities and villages, its history and ancient custom, its people and its soul, its meaning in our world.

It is #38 in the recent Modern Library list of nonfiction classics of the 20th century:

www.modernlibrary.com

www.modernlibrary.com

The New York TImes reviewer wrote:

"Black Lamb and Grey Falcon" bears the travel-book subtitle of "A Journey Through Yugoslavia," and it follows with consummate success the travel-book formula of history and description and characterization on a thread of personal experience. But it is safe to say that as a travel book it is unique. In two almost incredibly full-packed volumes one of the most gifted and searching of modern English novelists and critics has produced not only the magnification and intensification of the travel book form, but, one may say, its apotheosis. Rebecca West's "Journey Through Yugoslavia" is carried out with tireless percipience, nourished from almost bewildering erudition, chronicled with a thoughtfulness itself fervent and poetic; and it explores the many-faceted being of Yugoslavia -- its cities and villages, its history and ancient custom, its people and its soul, its meaning in our world.

It is #38 in the recent Modern Library list of nonfiction classics of the 20th century:

The Modern Library | Random House Publishing Group

Last edited: