AE35Unit

]==[]===O °

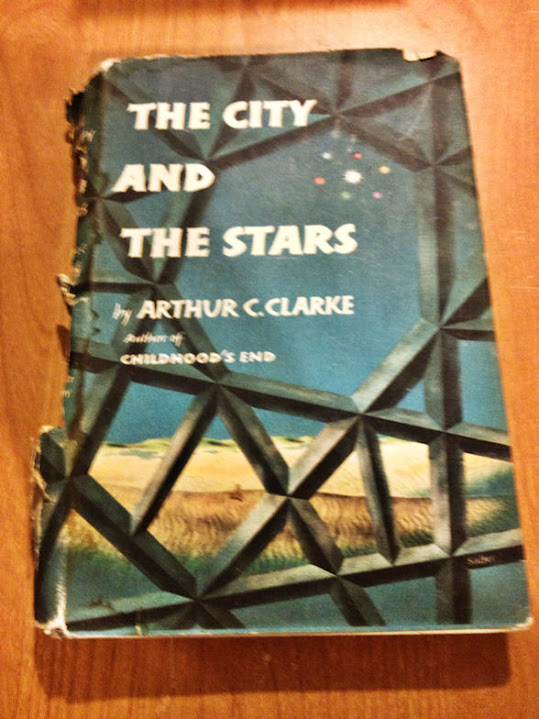

Great book.... her's my 1956 edition...

wow that looks well loved!

Great book.... her's my 1956 edition...

I've been trying to find an "affordable"..."The Nine Billion Names of God" hardcover book. Why is that one sooo expensive?

Commercially viable ICs from about 1960Newly employed by Texas Instruments, Kilby recorded his initial ideas concerning the integrated circuit in July 1958, successfully demonstrating the first working integrated example on 12 September 1958.

So I would argue the reverse is true for up to 1973 (The first Intel 4004 microprocessor shipped in 1971, Affordable "pre IBM" PCs by 1976)Golden Age SF writers massively overestimated progress in spaceflight and massively underestimated progress in computers.

ANY current computer design can be made with 1930s mechanical relays or electronic valves (tubes).

He followed this up with the extremely anemic and uninspired (IMO) Imperial Earth (1975)

| Thread starter | Similar threads | Forum | Replies | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Your Favourite Painting | Art | 14 | |

| D | What predictions of the future were your favourites? | Writing Discussion | 8 | |

|

|

Favourite Unusual Minor Historical Figures | History | 3 | |

| D | What's everyone's favourite grammar checker failures? | Grammar & Spelling | 4 | |

|

|

What is your favourite version of the Arthurian legend? | History | 34 |