I'm reading

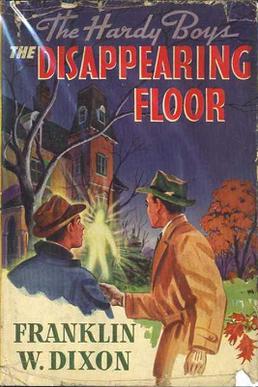

The Disappearing Floor, a Hardy Boys book by "Franklin W. Dixon," copyright Grosset and Dunlap 1964. I think this was the one and only Hardy Boys book that I owned as a boy (and what happened to that copy, I don't remember). The spooky cover art

appealed to me. Neither my parents nor my teachers tried to inculcate in me a taste for the eerie. It is a bit of a mystery why it developed in me and not in some of my peers -- like the taste for science fiction.

I'm reading only a few pages of this at a time. Like some movies of the past few years, it moves too fast for me. My imagination has been "trained" to respond so as not necessarily to require a great deal of detail in order to evoke an appearance and atmosphere. Tolkien refers to this kind of thing in his "On Fairy-Stories" essay somewhere. The problem with the Hardy Boys book is that the narrative flows along with dramatic episodes constantly popping up. C. S. Lewis complained:

"If to love Story is to love excitement then I ought to be the greatest lover of excitement alive. But the fact is that what is said to be the most 'exciting' novel in the world,

The Three Musketeers, makes no appeal to me at all. The total lack of atmosphere repels me. There is no country in the book--save as a storehouse of inns and ambushes. There is no weather. When they cross to London there is no feeling that London differs from Paris. There is not a moment's rest from the 'adventures': one's nose is kept ruthlessly to the grindstone. It all means nothing to me." (from his essay "On Stories")

Lewis also said that unliterary readers "demand swift-moving narrative. Something must always be 'happening'. Their favorite terms of condemnation are 'slow', 'long-winded', and the like. ...As the unmusical listener wants only the Tune, so the unliterary reader wants only the Event. The one ignores nearly all the sounds the orchestra is actually making; he wants to hum the tune. The other ignores nearly all that the words before him are doing; he wants to know what happened next. He reads only narrative because only there will he find an Event. ...he likes speed because a very swift story is all events" (from Chapter Four of

An Experiment in Criticism, the little book that I occasionally plead with Chronsfolk to read and which I think would delight many).

It is a reader like this who is liable to be most pleased by

The Disappearing Floor, and I suppose most children are "unliterary readers" much of the time at first -- although I wonder whether even quite young readers don't often enjoy also the sounds of words and their conjuring powers more than might be supposed.

I'm sure I liked

The Disappearing Floor at around age 10. A half-century later, when I require more than a fast-moving sequence of adventures, I think I'm contributing quite a lot to make up for the book's deficiency in everything but adventures set forth with competent diction. (Oh, there is a little bit also of amusing characterization with the boys' aunt. But aside from names I can't tell 17-year-old Joe and 18-year-old Frank apart.) If I were to read the book at the speed permitted by its modest vocabulary, I could whip through it in short order, but with a strong desire to drop it because I have so little investment in it.

It remains to say that the eerie cover art does rather more than justice to the book's contents. The scene with the apparition goes by quickly and conjures very little mood. The incident obviously will relate in some way to a gang of jewel thieves, a pretty mundane concept.

Lewis also writes about how unliterary readers often require stories that invite them to imagine themselves as glamorous, or wealthy, or strong and heroic, etc. Clearly the Hardy Boys are meant to be a boy's daydream of what he'd like to be: free to come and go as he pleases, able to stay out late at will, able to drive a fast car, etc. The boys' father is a detective -- what boy wouldn't have loved for his dad to be a prosperous private eye? And good food is always forthcoming -- a "hearty breakfast of bacon, eggs, and homemade muffins" on p. 18, a "hearty lunch" on p. 26). Girls? Well, "Joe grinned at Iola, whom he considered very attractive" (p. 23). But girls are kept in the background.

By the way, it appears the original version of the book dates to 1940.