paeng

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 22, 2019

- Messages

- 559

I started researching on the works after a student needed to use his trilogy for a senior thesis, and a few years before the films started coming out.

I found the articles (I've been trying to keep copies of online articles I read and used since the late 1990s, and cataloged them using DiskDB), and the one I was referring to isn't by but about Shippey. It's no longer available at TNR unless one subscribes, I think:

newrepublic.com

newrepublic.com

but someone shared the content here more than two decades ago:

www.cheftalk.com

www.cheftalk.com

The article also has references to Wagner and Tolkien's prose, which may be seen as both noble but also "gimcrack".

Some more:

www.christianitytoday.com

www.christianitytoday.com

www.newyorker.com

www.newyorker.com

www.today.com

www.today.com

Finally, this piece from Alex Ross talks about not only one of the movies but its music composer, and in light of Wagner, and with that Tolkien and Wagner, and Tolkien's background:

I found the articles (I've been trying to keep copies of online articles I read and used since the late 1990s, and cataloged them using DiskDB), and the one I was referring to isn't by but about Shippey. It's no longer available at TNR unless one subscribes, I think:

Bored of the Rings

J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century by Tom Shippey (Houghton Mifflin, 348 pp., $26) Click here to purchase the book.J.R.R. Tolkien's is indeed an extraordinary story, delightful in its improbability. Here was a quiet scholar, conservative, devout, nostalgic for a bygone rural way of life...

but someone shared the content here more than two decades ago:

Bored of the Rings

But finally it is what is left out of The Lord of the Rings that makes one wonder if this is really a book for adults. Tolkien invented his own mythological world, but it lacks the dignity and the sinew of a real mythology, for it is without religion and essentially without sex. Hobbits may have fur at the bottom of their legs, but they have seem to have no balls at the top; and that pretty much goes for the rest of Middle-earth, too. The women in The Lord of the Rings are few and pallid, while The Hobbit has no female characters at all: even the giant spiders are regarded by Bilbo as male (the narrative voice uses the unsexed pronoun "it"). The film of The Lord of the Rings seems to have tried to beef up the female quotient; but it was surely an uphill struggle. If one is to regard The Lord of the Rings as a book for adults, what disturbs is not so much the absence of women, perhaps explicable in an adventure story of this kind, as the absence of desire. In this work that presents itself as the representation of a whole world, there is hardly any awareness that we are sexual beings.

And that is not all that is missing. Tolkien was a devout Roman Catholic of conservative type, and he was sensitive to the charge that his Middle-earth was religionless. He replied that The Lord of the Rings was "a fundamentally religious and Catholic work." But that does not get around the difficulty: even if it can be shown that The Lord of the Rings is religious as a book--and I doubt whether even this is true in more than the superficial sense that it concerns a struggle of good against evil--the objection is that the people within the story have no religious beliefs or practices, and are thus unlike any real human society. Tolkien always insisted, and rightly, that his work was not an allegory, but the construction of a self-subsistent world with its own history. The trouble is that it is an emotionally impoverished world, in which the blood runs very thin.

The article also has references to Wagner and Tolkien's prose, which may be seen as both noble but also "gimcrack".

Some more:

Tolkien and the flight from modern life

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring is the first part of the trilogy adapted from J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy epic. It concerns an imaginary world in which unlikely heroes undertake a quest against the powers of Sauron, the personification of evil and darkness, by destroying the ring...

www.wsws.org

All of The Lord of the Rings is an elegy for the past, suffused with longing for the return to a better time, a golden age from which history is moving ever further away. As the elf Legolas laments: “Alas for us all! And for all that walk the world in these after-days.” In every sense the fantasy is a dirge looking backwards from the afterdays, that is, from the time after mankind’s fall from grace.

Tolkien’s outlook was bound up with rejecting the possibility of the progress of civilisation. Attacking such conceptions, according to his children, he would firmly say: “Progress to what?”

Tolkien’s magic diminished

The Return of the King, the third movie in director Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, has been released worldwide and established new records at the box office. Very few of its audiences would be new to the saga—the two previous films having won many enthusiastic adherents...

www.wsws.org

Tolkien’s life-long work was to weave a vast tapestry of an imaginary world, of which The Lord of the Rings was only a part. His artistry was mediated through his academic training as an expert in ancient languages—including Middle English and Icelandic—and the tales of antiquity.

His entire imaginative project made up for a deficiency he felt was manifested in English tradition. In this sense he was seeking to consciously elaborate a complete history, to enable him to seed the past at will with a more satisfying alternative—in his opinion English society had gone wrong from the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066. And it was through the stalwart efforts of his main characters, the hobbits and their fellowship, that Tolkien spun his fantastic notions of regenerating the present by recourse to a mythical past (see “Tolkien and the flight from modern life”).

Tolkien: Man Behind the Myth - Christianity Today

At odds with his age, he created another.

The 1960s brought not only fame but cultural change, invading even the great bulwark of traditionalism, the Roman Catholic Church. At one Vatican II-inspired Mass, Tolkien found the innovations too much for him. Disappointed by changes in the Mass's language and the informality of the ritual, he rose from his seat, made his way laboriously to the aisle, made three low bows and stomped out.

Much to the conservative Tolkien's chagrin, in the mid- to late 1960s the drug and political Left especially embraced his mythology. Afraid that such readers might create a sort of "new paganism" around his legendarium, Tolkien spent much of the last decade of his life clarifying its theological and philosophical positions in the work that became The Silmarillion.

The Anti-Tolkien

Michael Moorcock once wrote, “I think of myself as a bad writer with big ideas, but I’d rather be that than a big writer with bad ideas”

Not even Tolkien’s vast philological scholarship, his deep knowledge of mythology, and his world-building skills could impress what Moorcock and company saw as a troublesome infantilism inherent in Tolkien’s work. In a 1971 essay in New Worlds, the writer M. John Harrison acknowledges Tolkien’s position as the first and last word in fantastic fiction, but begs readers to look more closely, where they will see not the “beautiful chaos of reality,” but “stability and comfort and safe catharsis.” In 1978, Moorcock did a more thorough takedown in an essay called “Epic Pooh,” in which he compares Tolkien and his hobbits to A. A. Milne and his bear.

But the message was not getting through. In 1973, long before Tolkien’s characters would become internet memes and Lego figures, the British don died and left behind a pop culture landscape that was quickly being populated by elves, orcs, and hobbits. Tolkien could be found in songs, Harvard Lampoon parodies, and hippie slogans (“Frodo Lives!”). By the early nineteen-eighties, “The Hobbit” and the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy had spawned not only adaptations in the form of cartoons and animated motion pictures, but had established the dominant flavor of fantasy books, games, and films.

Why I hate ‘The Lord of the Rings’

It’s long, it’s boring and you could drive a Balrog through the plot holes. By Larry Terenzi

All action, no story movement. Where Fellowship was bogged down in exposition, “The Two Towers,” for all of its action and sense of momentum, likewise accomplishes little in the way of actual movement. Frodo and Sam begin the movie looking at the distant belching of Mount Doom – and that’s how they end it. In between, they do find Gollum, a CGI-character ironically infused with more soul than the live actors. He’s essentially a junkie who says the word “precious” way too often, yet amidst the movie’s chaos and circular wandering, he’s the only character to actually come up with a plan. Legolas, Gimli and Aragorn, meanwhile, kill Orcs at an ever faster rate. In the nadir of the series, Merry and Pippin, the Cheech and Chong of Middle Earth, hug a walking, verse-spouting tree in one of the most clock-stopping sequences put to film.

As if they’re not long enough, both movies follow the recent and so very greedy trend, see “Kill Bill” and the middle “Matrix” movie, of just ending – nearly in mid-sentence. How would you like this article to have ended three paragraphs ago? Don’t answer that. Yes, they’re segments of a whole but I didn’t put my satisfaction on the two-year installment plan. Each movie should offer at least a taste of closure, rather than be content with itself as a single frustrated act of an epic designed to suck 30 bucks from my billfold.

Finally, this piece from Alex Ross talks about not only one of the movies but its music composer, and in light of Wagner, and with that Tolkien and Wagner, and Tolkien's background:

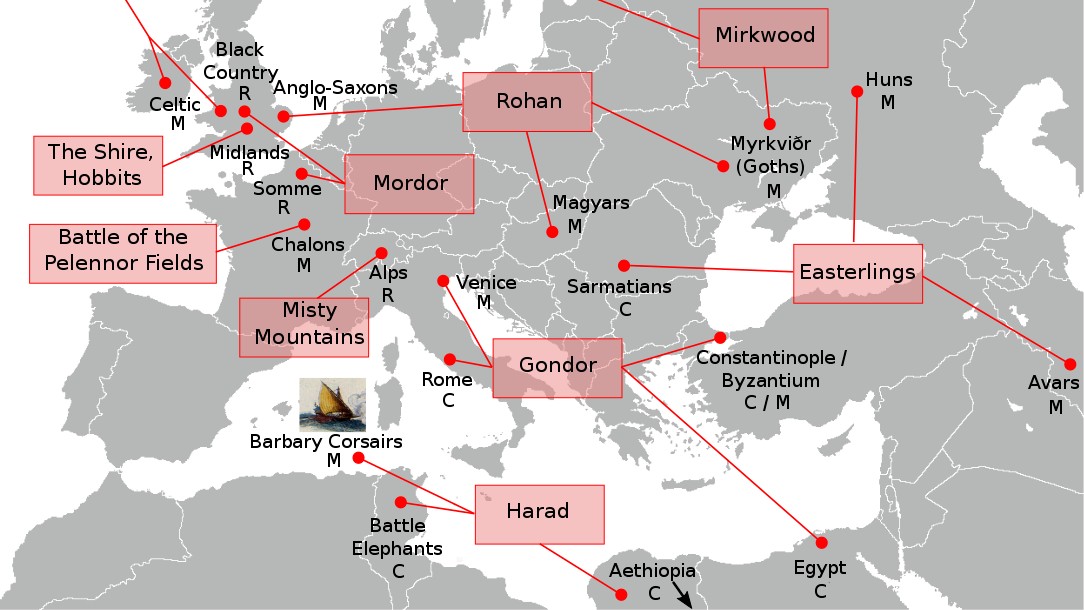

It is surely no accident that the notion of a Ring of Power surfaced in the late nineteenth century, when technologies of mass destruction were appearing on the horizon. Pre-modern storytellers had no frame of reference for such things. Power, for them, was not a baton that could be passed from one person to another; those with power were born with power, and those without, without. By Wagner’s time, it was clear that a marginal individual would soon be able to unleash terror with the flick of a wrist. Oscar Wilde issued a memorable prediction of the war of the future: “A chemist on each side will approach the frontier with a bottle.” Nor did the ring have to be understood only in terms of military science. Mass media now allowed for the worldwide destruction of an idea, a reputation, a belief system, a culture. In a hundred ways, men were forging things over which they had no control, and which ended up controlling them.

Tolkien began “The Lord of the Rings” in the wake of the First World War, whose carnage he experienced firsthand, and he finished it in the wake of the Second. In both wars, he witnessed the wedding of Teutonic mythology to German military might. He bemoaned how the Nazis had corrupted “that noble northern spirit.” You could see “The Lord of the Rings” as a kind of rescue operation, saving the Nordic myths from misuse—perhaps even saving Wagner from himself. Tolkien tried, it seems, to create a kinder, gentler “Ring,” a mythology without malice. The “world-redeeming deed,” in Wagner’s phrase, is done by the little hobbits, who have no territorial demands to make in Middle-earth and wish simply to resume their gardening. In the end, the elves give up their dominion, just as, in Wagner, the gods surrender theirs. Yet it is a peaceful transfer of power, not an apocalyptic one. The story ends not with the collapse of Valhalla but with the restoration of a wasted world.