Ah -- yes, here is Arthur Machen on Sir Walter Scott (from Far-Off Things):

It comes to my mind that I must by no means forget Sir Walter Scott and all that he did for me. And to get at him it is necessary that we enter the drawing-room at Llanddewi. I was amused the other day to see in an old curiosity shop near Lincoln's Inn Fields amongst the rarities displayed small china jars or pots with a picture of two salmon against a background of leafage on the lid. I remember eating potted salmon out of just such jars as these, and now even in my lifetime they appear to have become curious. So, perhaps, if I describe a room which was furnished in 1864 that also may be found to be curious. I may note, by the way, that we always applied the word "parlour"—which properly means drawing-room, and is still, I think, used in that sense in the United States of America—to the dining-room, which was also our living room for general, everyday use. So Sir Walter Scott speaks of a "dining-parlour," and Mr. Pecksniff, entering Todgers's, of the "eating-parlour." And now the word only occurs in public-houses, in the phrase "parlour prices," and even that use is becoming obsolete.

But as for the Llanddewi drawing-room: the walls were covered with a white paper, on which was repeated at regular intervals a diamond-shaped design in pale, yellowish buff. The carpet was also white; on it, also at regular intervals, were bunches of very red roses and very green leaves. In the exact centre of the room was a round rosewood table standing on one leg, and consequently shaky. This was covered with a vivid green cloth, trimmed with a bright yellow border. In the centre of the cloth was a round mat, apparently made of scarlet and white tags or lengths of wool; this supported the lamp of state. It was of white china and of alabastrous appearance, and it burned colza oil. One had to wind it up at intervals as if it had been a clock. In the sitting-room, before the coming of paraffin, we usually burned "composite" candles; two when we were by ourselves, four when there was company.

Over the drawing-room mantelpiece stood a large, high mirror in a florid gilt frame. Before it were two vases of cut-glass, with alternate facets of dull white and opaque green, of a green so evil and so bilious and so hideous that I marvel how the human mind can have conceived it. And yet my heart aches, too, when, as rarely happens, I see in rubbish shops in London back streets vases of like design and colour. Somewhere in the room was a smaller vase of Bohemian glass; its designs in "ground" glass against translucent ruby. This vase, I think, must have stood on the whatnot, a triangular pyramidal piece of furniture that occupied one corner and consisted of shelves getting smaller and smaller as they got higher.

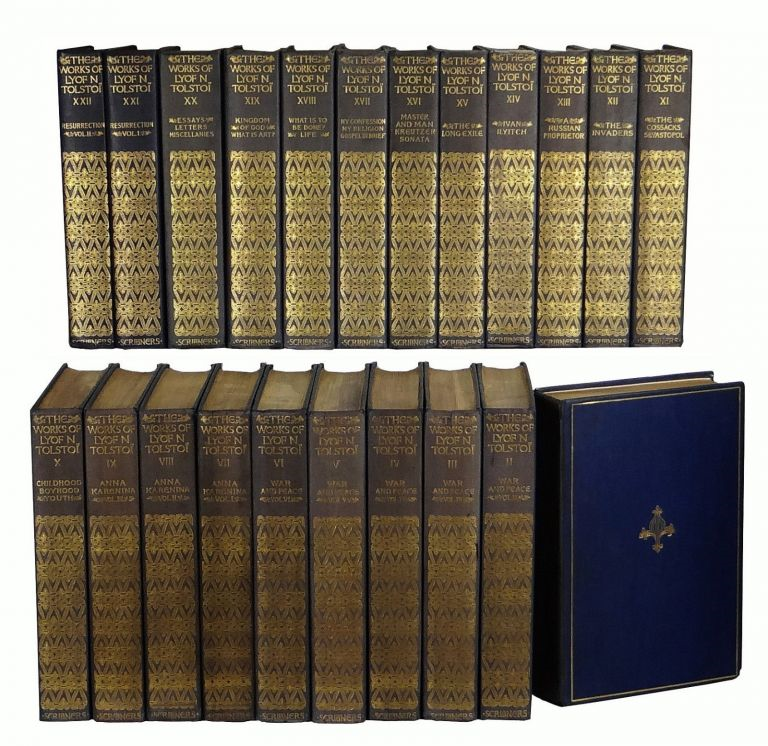

Against one wall stood a cabinet, of inlaid wood, velvet lined, with glass doors. On the shelves were kept certain pieces of Nantgarw china, some old wine-glasses with high stems, and a collection of silver shoe-buckles and knee-buckles, and two stoneware jugs. The pictures—white mounts and gilt frames—were water-colours and chromo-lithographs. Against one of the window-panes hung a painting on glass, depicting a bouquet of flowers in an alabaster jar. There was a plaster cast in a round black frame, which I connect in my mind with the Crystal Palace and the Prince Consort, and an "Art Union," whatever that may be: it displayed a very fat little girl curled up apparently amidst wheat sheaves. A long stool in bead-work stood on the hearthrug before the fire; and a fire-screen, also in bead work, shaped like a banner, was suspended on a brass stand. On a bracket in one corner was the marble bust of Lesbia and her Sparrow; beneath it in a hanging bookcase the Waverley Novels, a brown row of golden books.

I can see myself now curled up in all odd corners of the rectory reading "Waverley," "Ivanhoe," "Rob Roy," "Guy Mannering," "Old Mortality," and the rest of them, curled up and entranced so that I was deaf and gave no answer when they called to me, and had to be roused to life—which meant tea—with a loud and repeated summons. But what can they say who have been in fairyland? Notoriously, it is impossible to give any true report of its ineffable marvels and delights. Happiness, said De Quincey, on his discovery of the paradise that he thought he had found in opium, could be sent down by the mail-coach; more truly I could announce my discovery that delight could be contained in small octavos and small type, in a bookshelf three feet long. I took Sir Walter to my heart with great joy, and roamed, enraptured, through his library of adventures and marvels as I roamed through the lanes and hollows, continually confronted by new enchantments and fresh pleasures. Perhaps I remember most acutely my first reading of "The Heart of Midlothian," and this for a good but external reason. I was suffering from the toothache of my life while I was reading it; from a toothache that lasted for a week and left me in a sort of low fever—as we called it then. And I remember very well as I sat, wretched and yet rapturous, by the fire, with a warm shawl about my face, my father saying with a grim chuckle that I would never forget my first reading of "The Heart of Midlothian." I never have forgotten it, and I have never forgotten that Sir Walter Scott's tales, with every deduction for their numerous and sometimes glaring faults, have the root of the matter in them. They are vital literature, they are of the heart of true romance. What is vital literature, what is true romance? Those are difficult questions which I once tried to answer, according to my lights, in a book called "Hieroglyphics"; here I will merely say that vital literature is something as remote as you can possibly imagine from the short stories of the late Guy de Maupassant.